In the first instalment of the Historic Environment Forum’s Sector Resilience Interviews series focussed on the theme of Governance, we hear from Ari Volanakis, PhD researcher.

Please tell us a bit about yourself and your role.

I am Ari Volanakis, PhD researcher at the Institute for Sustainable Heritage at UCL, and an experienced cultural heritage management professional. The Institute for Sustainable heritage delivers ‘…sustainable solutions to real-world cultural heritage problems through ground-breaking, cross-disciplinary research and innovative teaching for future heritage leaders’ https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/heritage/.

I have worked as Operations manager for the National Trust, as Heritage Area Manager for Lincolnshire County Council, Heritage Development manager at Rutland County Council, project manager for Heritage Fund funded projects and provided consultancy for the ‘concerned about closure’ Museums Development programme. I have been a volunteer, trustee, and have previous commercial management experience. My work is driven by my passion and experience, combining a heritage heart and a business brain.

My doctoral research develops a knowledge management design for the cultural heritage sector https://www.avculturalheritage.org/. Perhaps you have experienced the difficulties of finding the most relevant and up-to-date information when you must perform a cultural heritage operation such as reviewing your policies or governance documents, setting up digital ticketing or 3d virtual reality tours, applying for grants or managing a project, evaluating economic impact, developing self-generating income streams, plan people’s professional development, updating quinquennial reports or the collections’ online system? How stressful has it been, how long have you wasted looking?

It seems the problem now is an information overload, especially when the operational needs, visitor expectations, working patterns, financing, historic and wider environment, and technology all change at such a rapid rate. One cannot know which knowledge resource is more recent or valid. The problem becomes more difficult as cultural heritage organisations need knowledge to deliver double the operations compared to commercial businesses: to grow organisational sustainability as a business, and to provide a participatory curating service. Cultural heritage organisations are professionally curating (creating, collecting, storing, conserving, and communicating) not only heritage assets and cultural values, but also knowledge about cultural heritage. Paradoxically though, whilst cultural heritage organisations curate knowledge for the public, thousands of them do not have the organisational knowledge they require to manage their rapidly changeable and demanding operations.

And the problem does not apply to one type of organisation only; a whole range of organisations face similar difficulties, shown in the image below:

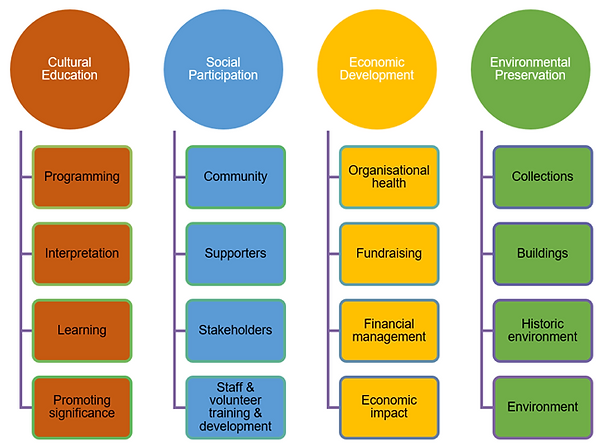

16 common operations categories (rectangles in the image below) are observed across the full spectrum of the above cultural heritage organisations. These are placed within the four common objectives (in the circles) as found in cultural heritage governance documents and annual reports.

(To read a summary description for each operation follow the link within https://www.avculturalheritage.org/useful-information)

This framework provides a starting point to study what knowledge is present for each of the 16 operations, how it is created or sourced, and whether it is up-to-date. And, what is provided by sector support organisations, what isn’t, how it is accessed, and whether it is used and beneficial.

The pilot study finds only 3% of present and updated knowledge across the 16 operations in cultural heritage organisations. This mere 3% however is associated with a 10.2% higher performance across the four objectives. If we could find a design to grow that 3% of knowledge in cultural heritage organisations, to say 30%, or 60%, the improvement in performance would be extraordinary. And the reduction of stress and wasted time would also be significant.

Such a design requires understanding of the complicated nature of cultural heritage work by staff and volunteers. It also requires trust across teams, organisations, and the sector. Knowledge exists in often overly elaborate or boring manuals in printed and digital formats (explicit knowledge), and within people with extensive experience (tacit knowledge). Using Nonaka’s knowledge model and Cooperrider’s Appreciative theory, the design aims to bring together explicit and tacit knowledge and to appreciate what we do well; to make recorded knowledge present and accessible so we can learn and grow, and we then enrich the recorded knowledge with our experience in a continuous cycle so we can grow more. This is after all what cultural heritage is all about.

We might also find synergy opportunities, for example libraries might have documentation management processes that theatres do not have, but theatres might have more developed ticketing systems. And both can be beneficial to museums, which can share conservation and interpretation knowledge, for example. The result would be a more efficacious, less expensive, and less stressful way to improve performance across the sector. Furthermore, recorded knowledge is ineffective without networking, communication, and mentoring.

The research objective therefore is to develop an organisational knowledge design for cultural heritage; a synergic design (curating organisations and sector support working together) and methodical application (across the sector’s common operations) of manuals, toolkits, and associated software, that empower individuals and teams, and improve organisational performance (delivery of cultural, social, economic, and environmental objectives).

What can you tell us about your work in relation to Governance? What does this work aim to achieve?

Governance in this research sits within the Economic Development objective and particularly within the Organisational Health operational drum in the previous image, being consistent with the Arts Council’s accreditation scheme. It also sits within the Staff and Volunteer development operational drum, recognising the need to appreciate, look after, support and develop the people who represent our organisations. The Historic Environment Forum’s Resilience plan on Governance aims to support business plans and governance models ‘through greater sharing of experience and best practice’ (p7) (I also use the alternative term for best practice of ‘successfully demonstrated’ practice (O’Dell, Grayson and Essaides, 1998, p. 13)). Sharing tacit knowledge (experience) and explicit knowledge (recorded best practice) are core outputs of the knowledge management design being developed by this research. The proposed design will enable easier creation, sourcing, sharing, and updating of recorded knowledge across the sector, and works towards building trust, networking, and open sharing culture in a more unified cultural heritage sector. In the recently published paper on the long-term impact of COVID-19 on heritage, I highlight ‘the significance of the sector coming together during the pandemic to share knowledge and provide support through its networks….also…how important it is for such unity not to be lost but to be harnessed to support ongoing organisational sustainability and better preparedness for future crises’ (https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/7/6/152, pp. 3240-1).

What contribution will this make towards resilience in the heritage sector?

The Historic Environment Forum’s Resilience plan defines resilience through four characteristics: (1) having the right knowledge and expertise, (2) being appreciated and appropriately-resourced, (3) actively serving the community, and (4) being well-connected and collaborative. The first characteristic is perfectly matched with my research content of having accessible and up-to-date knowledge to deliver our operations. For the second characteristic, the organisational knowledge across the Promotion and Stakeholders operational drums enables being appreciated through marketing and networking. The third characteristic of actively serving the community is supported by all four objectives of my design, involving cultural and social participation operations, economic development, and environmental preservation. The final characteristic of being connected and collaborative is supported by a number of the social operational drums (community, supporters, stakeholders), and from the Organisational Health drum and its Governance aspects. Furthermore, the entire design is underpinned by building trust, and benefiting from collaborative curation (creating, collecting, storing, conserving, and communicating) of organisational knowledge within our sites and across our organisations.

What does success look like for your work?

The research data will be analysed during winter 2024-2025 and the proposed design will be published during 2025. Discussions with leading heritage organisations will be taking place to enable piloting and fully launching the design to benefit small and large organisations within the cultural heritage sector.

How can sector colleagues get involved or find out more?

You can take part in the research by completing the online questionnaire by 26th July 2024, on https://www.avculturalheritage.org/complete-the-questionnaire. It takes about 15 minutes, and your contribution will inform the beneficial design.

After 26th July, you can still get in contact directly and share views, on ucbqnav@ucl.ac.uk or arivolanakis.heritage@gmail.com.

Overall, what do you think is most crucial for ensuring a resilient heritage sector?

The knowledge design in my research supports the resilience plan, and particularly in relation to ‘better preparedness for future crises’ as mentioned in a previous question. But within the same sentence I also discuss ongoing organisational sustainability. Resilience is essential for riding the waves, and from that initial firm point we can aim for longer term organisational sustainability (see https://www.avculturalheritage.org/useful-information for a definition). Having a live knowledge bank, associated networking and knowledge management design will enable the sector to not only be reactive to crises, but also to plan proactively, wisely. The first big step of having resilience fuelled by a sector-wide knowledge design will lead to the ability to proactively manage change and be organisationally sustainable for the long term.

This Sector Resilience interview was shared by Ari as part of our Heritage Sector Resilience Plan activities.

If you’d like to contribute an interview as part of the series, follow the link below to find out more: